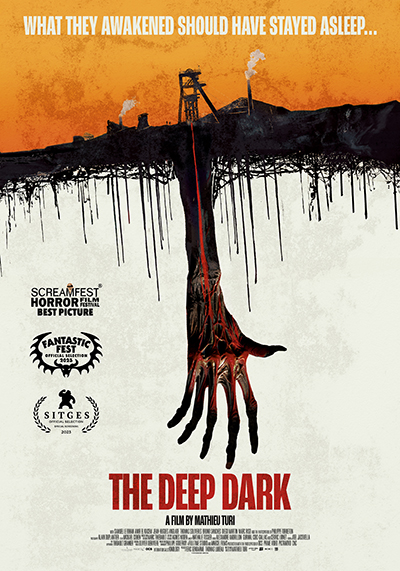

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Deep Dark (2023) Film Review

The Deep Dark

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Few occupations require as much trust and teamwork as mining. Down there in the dark, where devastating accidents can happen at a moment’s notice, the men who labour all day to scratch out the raw materials that fuel civilisation share traditions and superstitions which bind them together. They sing songs as they work. In its cage, a canary sings too – until it doesn’t. The miners with whom we begin this film, which screened as part of Glasgow Frightfest 2024, see the stiff little body of their yellow bird and realise that they must have opened up a pocket of gas. In comes a specialist to detonate it safely – according to the standards of their time – but he’s not prepared for the other thing he will encounter, down there in the dark.

Films about mining are inevitably made with an awareness that some members of their audience will be claustrophobic, and that a similar sensation can be induced in others – a clawing, desperate need to get out. Sometimes, however, sensations akin to that can develop in very different places. When Amir (Amir El Kacem) wakes up in his room in Morocco, it’s flooded with light. The thin curtains are moving in the breeze and beyond them he can see the vastness of the desert. but Amir wants to get out. He wants opportunity, control over his future. A friend tells him that if you can persuade a visiting company to hire you and take you to France, you can make money there just by picking up stones under the ground. With a teacher for a mother, Amir is already fluent in French, so he’s sure that he can make this happen, and he won’t take no for an answer.

Meanwhile, at mine number five – the one they call Devil’s Island – something is afoot. A mysterious professor (Jean-Hugues Anglade) is bribing officials with large sums of money to let him venture down into the depths for some unknown purpose. There’s a particular place he wants to get to, as if he were seeking something buried far below the surface. When he witnesses an impressive achievement by mining team leader Roland (Samuel Le Bihan, who conjures up, after all these years, something of the same quality of compromised heroism that viewers may remember from Brotherhood Of The Wolf), he decides that that’s the man whose team he wants to accompany him. Of course, that’s the team that Amir ends up assigned to.

Having established the threat, director Mathieu Turi takes his time to let us get to know the characters and the way they work. He quickly comes to appreciate how dangerous the mines can be, but nobody on the team is prepared for what happens next: for the place to which the professor will lead them, for the rock fall that will trap them, or for the thing they find down there. Trying to go along, to fit in, to please his new colleagues, Amir unexpectedly finds that his own, very different skills have value. The professor doesn’t share the racism of many of the others, and immediately takes an interest in him as somebody to whom he can explain aspects of his work. it soon becomes apparent, however, that the professor himself may be in too deep.

The specific context of this underground adventure means that the film doesn’t have quite as intense a claustrophobic feeling as many of its ilk. Little time is spent crawling through small spaces; we can reasonably assume that the air supply will last for a few days; but in these particular circumstances, the miners may struggle to last an hour. Despite their predicament, they have plenty of distractions. Assorted historical artefacts litter the area, and in case those don’t provide enough clues, there are also numerous messages and inscriptions – one in French, some in the Futhark alphabet, and some in more obscure characters.

The character interactions work well here. Turi has invested in top flight actors and it pays off. A fair bit of the budget has also gone into special effects. This results in some impressive set pieces, especially one involving the team’s blind white horse, Cartouche, but in other places one can’t help but feel that less would be more – some scenes have more lighting than is necessary in context and would be scarier if we couldn’t see quite as much detail. Similarly, whilst the explanation that the professor eventually delivers is a lot of fun and delighted the Frightfest crowd, the film might have been more successful by showing a bit more restraint. It depends too much on pre-existing tropes instead of feeling fully confident in its own ability to give viewers nightmares.

Lying behind all this, and equally nightmarish in its way, is the callous attitude of the mining company, which sees the men only as tools through which to profit and shows little concern for their lives. Roland works hard to protect his team above ground as well as below. Amir’s wide-eyed observation of the scale of the above-ground equipment could just as easily speak to the corporate structure within which he has found himself trapped. It mirrors the film’s later positioning of humankind as small and helpless, at the mercy of much greater forces. That particular horror trope has been used for over a century to send shivers down the spines of intellectuals, but working class people have to live with it every day.

It’s in this understanding of working life that the film really excels, and it’s refreshing to see working class characters given centre stage in a story like this. Overall, the film could do with some tightening up. it may have bitten off more than it can chew, but in doing so, it has provided some food for thought.

Reviewed on: 09 Mar 2024